Ancient Beauty Illuminates the Modern World

Salvēte, Amicī Meī

If you are reading this, you likely already know me in some way, and for that I am grateful, because that means that I know you in some way, too. Sitting down to write this, I loved that I would be writing to you, but I was a bit flummoxed by the seemingly paradoxical knowledge that if I am writing an introduction to myself for a reader who already knows me, how might that work? And then I realized that the whole point, the real point, the fine point, was to reveal my self to you in a way that you likely don't know, to share with you not who I am, exactly, but more the why of me, the genesis of the passion I have for goldsmithing. And that led me to think about what actually sparked it, and as soon as I moved back to THE one moment in time, I realized that in fact it had simply been the next ember, not the first kindling. Passion can rarely be defined well at all, but perhaps the history of my passion can be traced backwards along a remembered path of sparks that have illuminated the way to where I am and what I do now.

You've probably experienced how truly strange it is to realize that splintered moments of time or experience or sensation, things that seem random or disconnected in the moment, can come together to create something new, to reveal a way of seeing, to birth an idea. It is also wondrous to realize that a collection of those bits can rearrange themselves, as glass shards do in a kaleidoscope, so that a simple twist of the ring (or life), brings a wholly new picture into view. This is, I think, is what Robert Frost meant when he wrote that "way leads on to way".

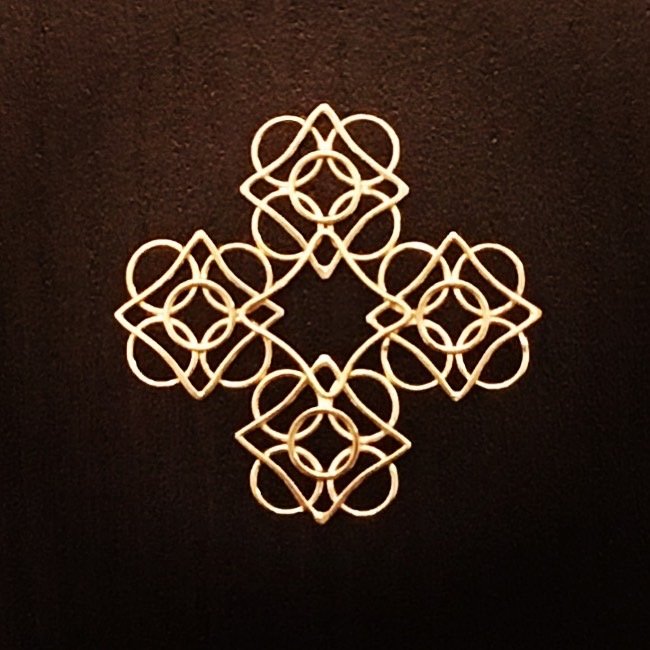

I state, rather boldly, that, inspired by the ancient world and created for the contemporary woman, my jewelry is, in both design and execution, a melding of antiquity and modernity, of symmetry and fluidity, of attention to detail and recognition of the whole. It is my truth, but what does that even mean? In writing this, I have come to realize that I can actually trace where I am now at my bench back to glass deer and the Brothers Grimm.

Why the Brothers Grimm? Bear with me. I learned to read when I was three and a half, and I only know this number because my mother often said that was the point at which I became wholly and utterly unmanageable unless I had a book in my hand.

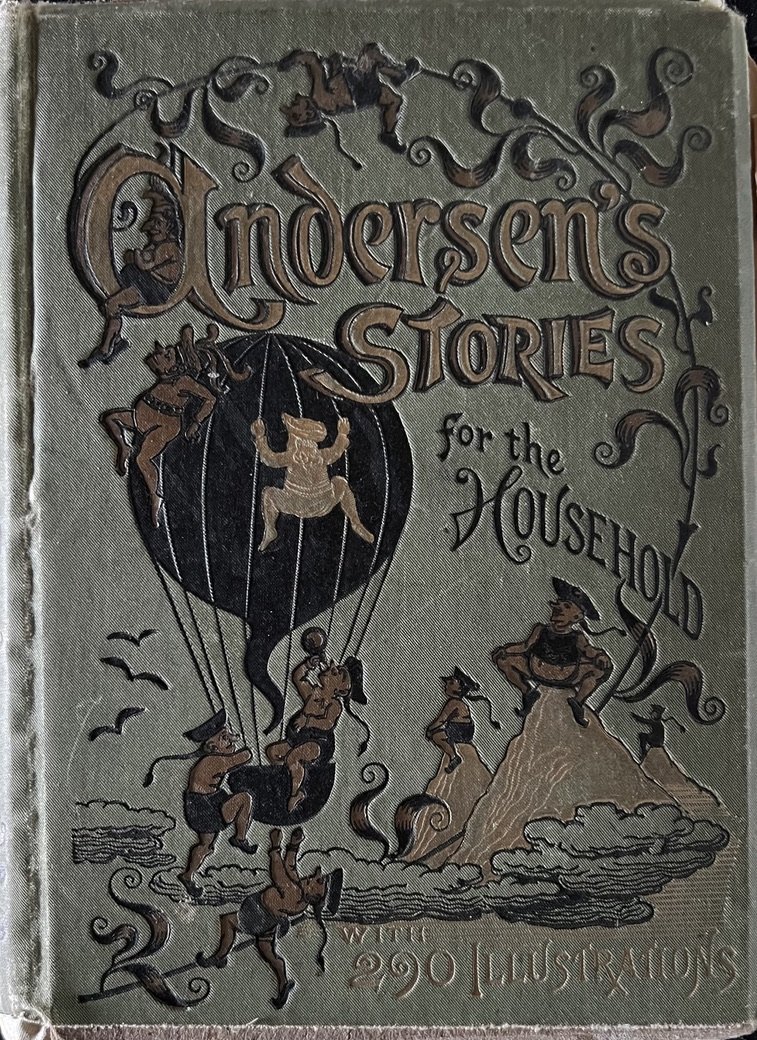

Andersen’s Stories for the Household (1891)

Those books were amazing, volumes gifted me by my eccentric uncle, many of them first editions from the late 1800s and early 1900s. Among them was a set of the original Oz books, begun by L. Frank Baum and then continued by his niece, Ruth Plumly Thompson, and beautifully illustrated by John R. Neill. This richly tapestried and widely ranging set basically ruined me for the movie version of the Wizard of Oz because the saga of Oz was so much richer than the cinematic adventures of Dorothy alone.

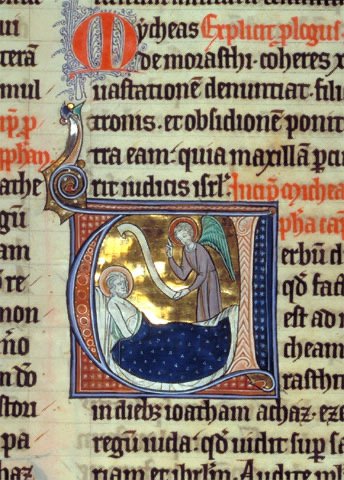

And then there was an 1890 edition of Grimm's Fairytales for Children (which were actually really grim, and very alarming, looking back on it) and a beautifully illustrated collection of Hans Christian Andersen's Stories for the Household (1891). The red shoes, the loaf of bread, the little mermaid - all of these completely captured my imagination through both word and image (but trust me when I say that Sebastian the Crab is NOT an original cast member...would that he were; he might have talked some sense into her).

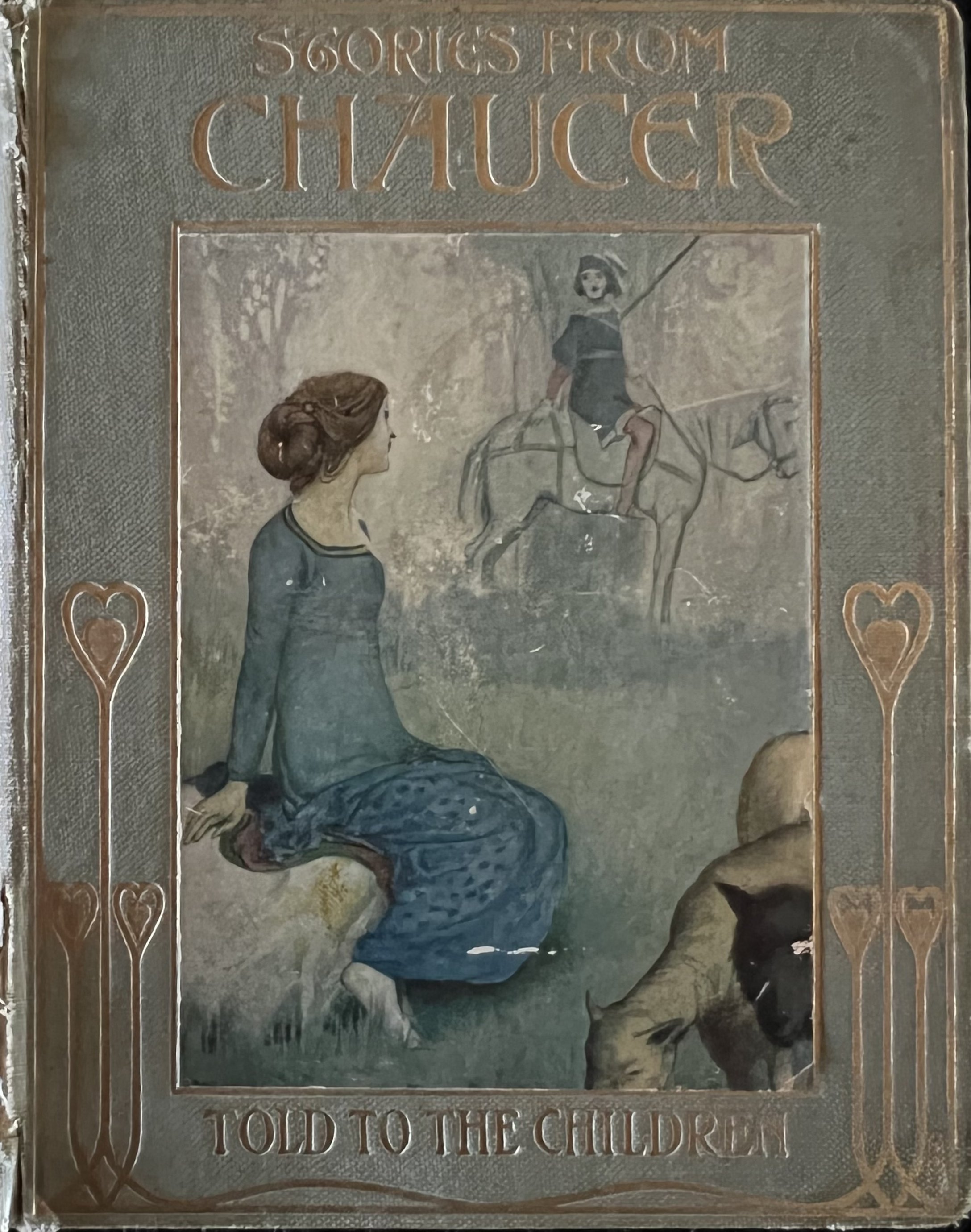

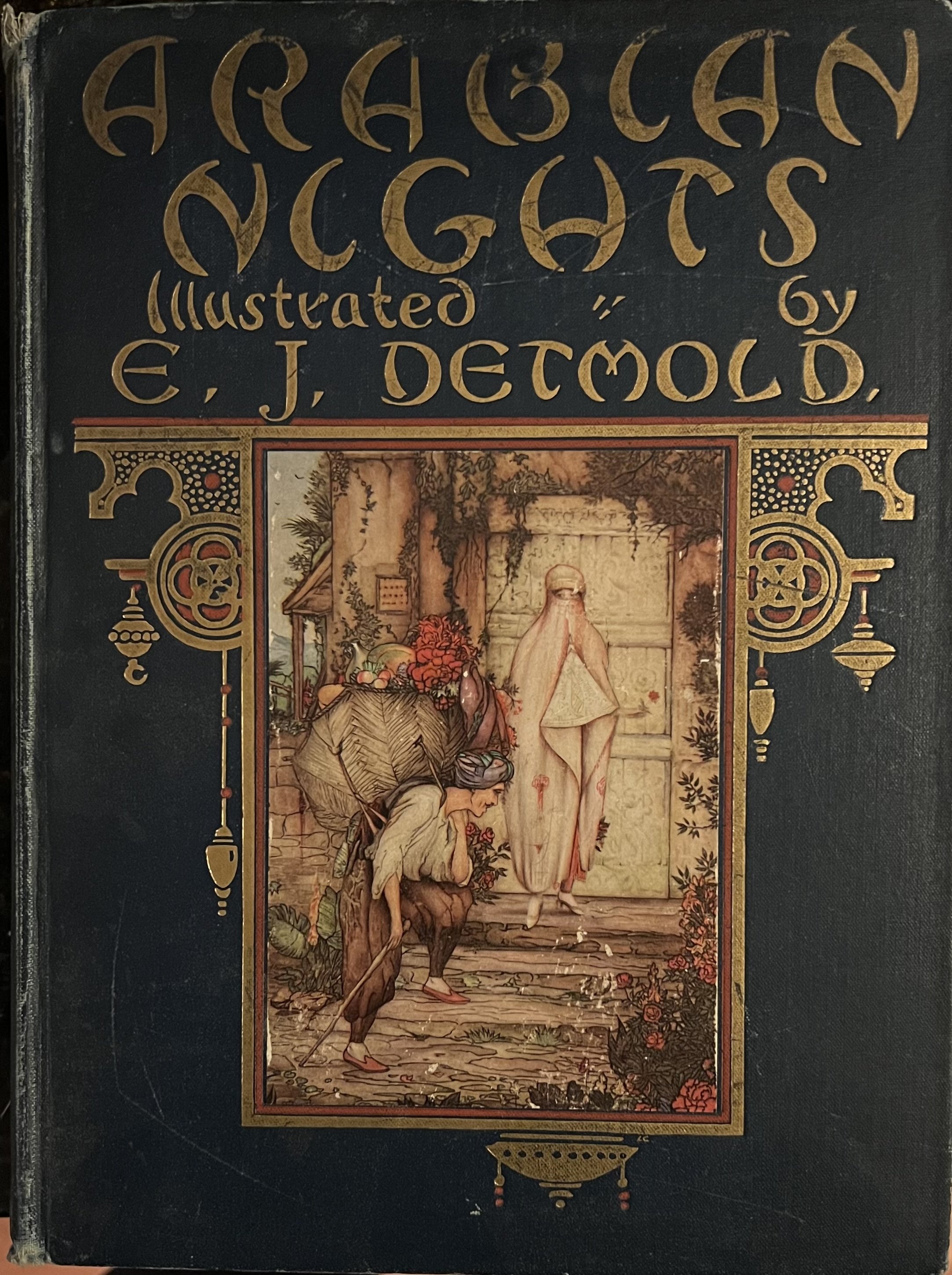

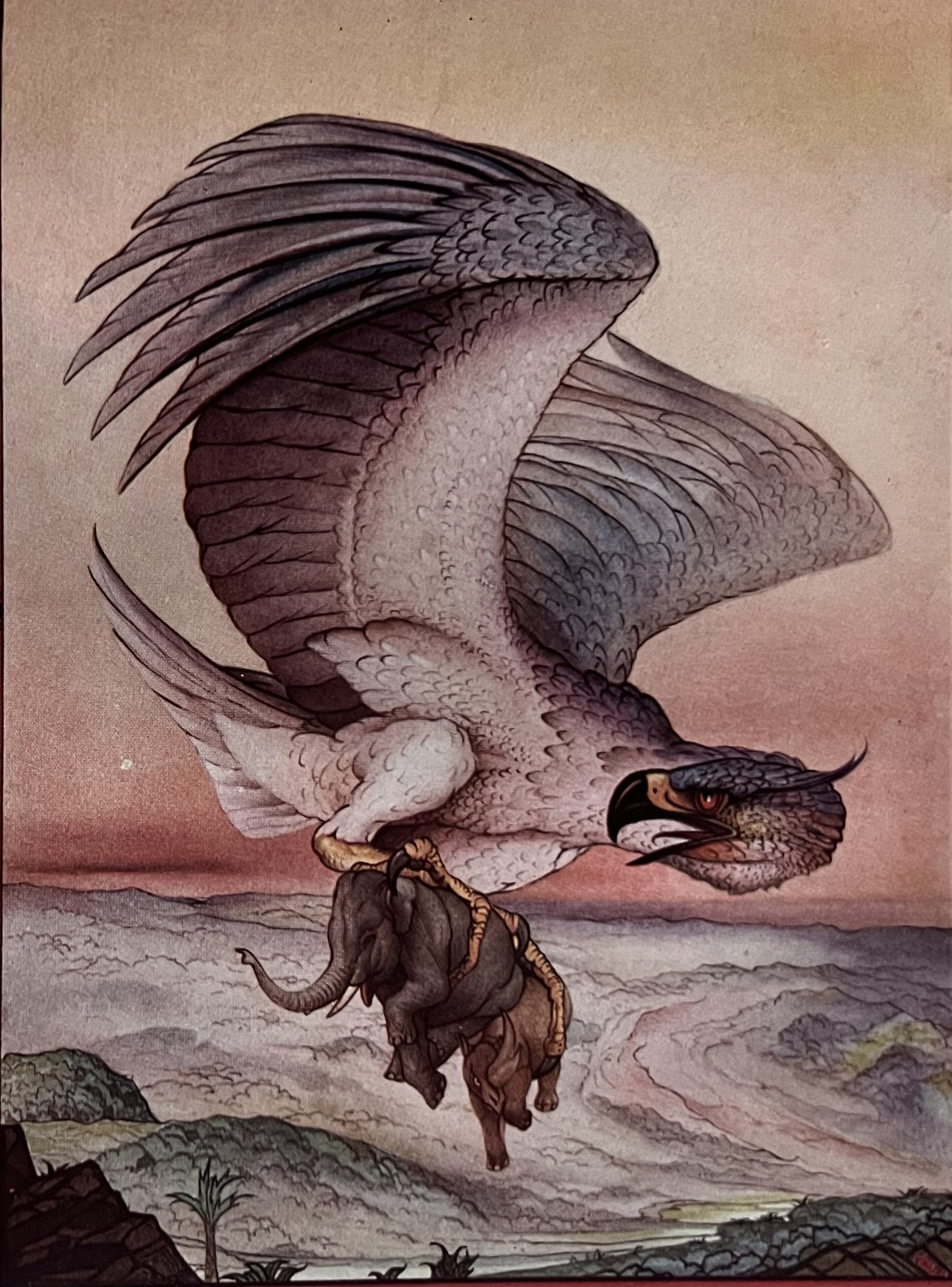

There was also a tiny copy of Chaucer's stories. I had no idea who Chaucer was but as it turns out the four tales in the volume were simplified versions of The Canterbury Tales and, to accompany this unknowing foray into the world of Middle English speakers, I had an illustrated version of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. At the time, I didn't know what a kirtle was, but I knew that the Lady wore a green one and I wanted it. Beyond that, a volume of The Arabian Nights introduced me to the mythology of the Middle East and the d'Aulaires' editions of Norse Gods and Giants and Book of Greek Myths brought me into the far-flung reaches of the Norsemen and the Greeks.

“The Ruhk Carries off the Elephant” (Arabian Nights, 1925)

Inspiration: the Drawing in of Breath

The illustrations in these books were from hand-drawn and hand-coloured plates by artists such as Arthur Rackham, Aubrey Beardsley and Walter Crane. They were richly detailed and fantastical. In them I found portals into the worlds of the books, and just the other night, as I was looking through that book of Chaucer's stories, a colour-plate of Constance from "The Lawyer's Tale" caught my eye.

Stories from Chaucer Told to the Children (1899)

What did I find worked into the fabric of Constance’s simple sleeves? Something very like a compass rose. Is that where the image first embedded itself in my mind, so that when I saw it later on medieval maps it was because I had been drawn there, to the middle ages and manuscripts precisely because of the imagery filtered through the imagination of a little mind? Way does lead on to way, yes?

I still have many of these books and, as an adult, I wonder at the extravagance of the gift my uncle made. These were important books, many of them first editions, all of them old, even in the late 1960s, and yet he gave them to me. To me. A little kid. And, as a little kid is wont to do, I read them and dogeared their pages; my parakeet ate the corners of some and I generally mistreated them without knowing what I held in my hands, but the adults didn't care. They let me devour the books, and I did, sometimes literally. Those early reading experiences certainly shaped my imagination and my life in ways that I couldn't begin to understand at the time. As I got older, I read everything I could find on all myths, not just the Graeco-Roman. When I discovered the gods and history of Egypt, I decided at the mature age of eight that I would become an archeologist when I grew up. The way was set. I was going to literally dig into the past and bring the ancient world up into the light. Antiquity would be my home and I just KNEW that I would spend my adult life among monuments and artifacts that I unearthed from the past.

Then, in 1975, I fell hard for jewelry the moment I stepped into an exhibit of Scythian gold-work. The jewelry was 3,000 years old; I was ten. It was love at first sight. Seeing these hand-wrought treasures, not in a book, but there, just behind glass, where I could almost touch them, deepened my connection to the ancient world. I went from seeing the ancient world in the magical macro - the large - the pyramids, the Parthenon, the Djinn, gods and goddesses, giants and Valkyrie - to seeing seeing humanity in the micro of found objects that fit so perfectly into small well-lighted places - cases and stands and kiosks - and much of those found objects was jewelry. Just the name "Scythian" excited me - it was new and tasted strangely on my tongue, sharp and vaguely spiced; I wondered if it was related to the scythe of the Grim Reaper (as it turns out, it is not - but it could have been, especially to my ten-year-old mind on fire with language and image and artifact and imaginings.) The world of the Scythians fascinated me. They were so different from the Greeks and the Romans, from the Egyptians, from the Persians, and the artifacts on display whispered to me from behind their muted glass of a world I had never envisioned.

As it turns out, the "Scythian" gold was Scythian in two ways. The Scythians, perhaps named thus by the ancient Greeks for their formidable prowess as archers, but whose name might also simply mean "nomad", were a loose collection of ethnically related tribes that ranged across the Pontic-Caspian steppe from about 900 to 200 BC. Presumed to have originated in the Iranian region, the Scythians were renowned horsemen, feared warriors and, as it turns out, collectors of beautiful gold ornaments, some of which they made and some of which they acquired through trade with the Black Sea Greeks. These comprise jewelry, to be sure, but also ornamentation for the shield, the sword, the quiver, the horse's tack, the horse itself. Even their drinking cups were plated with segments of goldwork. Some of the stunningly ornate pieces are clearly less culturally Scythian, as they depict the gods of the Greek pantheon and Greek daily life.

Gorytos (bow and quiver case) Cover

And then there are the more totemic pieces, which are perhaps more roughly constructed but no less beautiful because they speak to the Scythians as horsemen, hunters, warriors and nomads. Just as with the gorytos cover, these pieces are related to daily life. Although there is no question that only the wealthier Scythian's drinking cup or horse would have been embellished with gold ornaments, the fact that such items exist gave me a glimpse into what the Scythians held dear.

As a child, I couldn't see the delineation between the sets of artifacts, didn't know to say "Oh, that's clearly inspired by the Greeks" or "That must be a scene from Scythian daily life." To me, they were all simply parts of the most amazing treasure hoard I had ever seen outside an illustration of the inside of Aladdin's cave. Only much later, when on my own path to becoming a goldsmith, did I realize what exactly went into the hand-fabrication of these artifacts.

Tools, Tech and Artistry in the Ancient World

The skills of those ancient goldsmiths, which ranged from artistry and precision work ("with no tools," wails this modern goldsmith, "with no flex shaft or oxy/propane torch, with no saw and no drill, with no rolling mill....I caaaaaannn't!") to a healthy understanding of metallurgy and physics, continue to keep me under Auden's anxiety of influence and the influence of my own anxiety, which makes me wonder if I might ever do something like that even with all of the modern tools at my disposal?

First is metallurgy, the knowledge of how to alloy gold with silver and copper in just the right amounts to keep the gold pure and bright as the sun setting and how to create electrum from fine silver and gold. It continues with then migrating those alloys into forms that can actually be worked, and that can be through the pouring of an ingot, which can be hammered out into sheets or chiseled into wire or the casting of a mold in clay, stone, sand or wax. Melting didn't happen with convenient bottles of oxygen and propane fueling the flame. It happened over charcoal fires fed oxygen by lungs of the smith or a bellows.

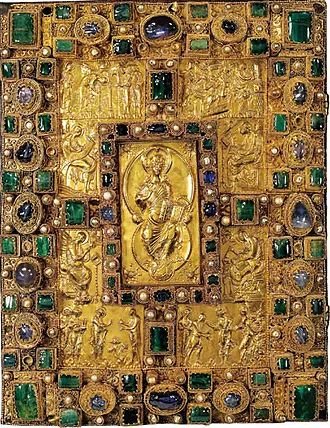

Wire these days is generally pulled through progressively smaller sets of holes in a tool-steel draw plate. Wire back then was most often chiseled off a sheet in the width and length needed. Sheets of metal were hammered progressively thinner, sometimes to the point where it became the thickness of tissue paper. Because gold is so malleable, a piece the size of a quarter can be beaten out into a sheet measuring one hundred square feet, and this is what John Donne means when he says that love is like gold whereby parting is not a "breach" but an "expansion/Like gold to airy thinness beat." By beating it out so thinly, the gold becomes leaf, which can be burnished onto surfaces ranging from other metal and wood to the gorgeously illuminated velum of mediaeval manuscripts.

And don't even get me started on interrasile chiseling, which looks like filigree or piercing until you realize that it is done not by adding in little bits of wire in a pattern or using a finely manufactured saw blade, but rather by using a mallet of some kind to whack a sharp tool so that small bits are essentially chiseled out of the sheet to make it look like the pattern has been pierced.

The processes of either raising or depressing the surface of sheet into shapes and patterns that create images are known as chasing and repoussé. Looking at the detail in the central piece of this Scythian pectoral, you find not just images but an entire story, one of men mending their clothes and of horses nursing their colts or being eaten by griffins ("GRIFFINS", the little girl whispers in wonder). The expertise and patience required of both techniques boggles my mind, especially when I consider the tools available then. Similarly, granulation, the process of creating patterns from tiny spheres of metal, and filigree, the process of creating patterns from tiny curls and twists of wire, are incredibly detailed and painstaking processes. And finally, whether it was fused or soldered, the flux didn't come in a plastic bottle but was rather a blend of copper salts, and the fire had to be consistent in temperature in order to bring the metals to the point of marriage without melting them down into each other.

Scythian Pectoral (center detail)

In writing this, I keep thinking that it's all incredible to the point of literally not being credible, but ancient goldsmiths were able, with the rudimentary tools available and more expertise than I will ever have in the seen or unseen universe, to do all of that and more.

As a child, though, all I saw was the sheer overwhelming beauty of the animal and vegetable motifs, of the gods and their adventures, of the martial skills for which the Scythians were known and feared. Together, the gold work of the Scythians told a little girl the story of a people long since vanished into history and of the amazingly skilled artisans who literally forged that story into artifacts that she could "read". It was quite a day at the museum.

Then, several years later, the international tour of King Tutankhamun's treasures came to LACMA, and I once again found myself pulled into antiquity. By then, I had begun taking Latin in middle school, an endeavour that, as you know, I continue to pursue through my torture of middle school boys. The beauties of the language, the intricacies and puzzles of the declensions and conjugations, the treasure hoard of vocabulary were and are the lingual equivalent of the Scythian and Egyptian treasures.

Paths Wend and the Soul Follows

For quite some time, I believed that I would become an archaeologist. I am sure that my parents silently despaired and thought to themselves, "Oh, lovely, well, she'll be living in our basement forever, then. Better clear it out early." But they never said that; they just continued to feed my need to know the ancient world through books and museums. I didn't go straight into college from high school, but rather took a full time job on the at USC Medical School campus when I was 17. Earning a paycheck was lovely, but to keep my mind working I signed up for a weekend seminar in cultural anthropology with a focus on the ancient world through a local community college and that was that. I was hooked on college and went to school full time from then on, working my day job at USC and attending classes at night from 6-10pm at Cal State LA.

After graduating, trying two years of law school at Loyola and finding myself desperately unsatisfied, I returned for a Master's in English, and that led me to pursue my PhD in medieval and modern war poetry (yes, I know, the basement apartment. Hush.) at the University of New Mexico. With my graduate work in Old English literature, I found a new treasure-hoard of inspiration in the gold-work of the ancient Celts, Vikings and Anglo-Saxons, as well as the Byzantine Empire.

I also discovered that Old English and Old Norse now vied with Latin for my attention, and I ended up completing my dissertation on the ethic of the war-band comitatus in Old English heroic poetry. (I have my fingers in my ears and I'm not listening to your laughter right now. I do NOT live in the basement, unless I'm chasing a deadline for creating jewels.)

While researching and writing my dissertation, I had the privilege to work with primary documents at the Imperial War Museum and the British Library in London as well as the archives at Cambridge and Oxford, but it was the British Museum, with its incredible collections of ancient gold-work, that ate up all of my free moments over those amazing summers of study and writing. I was drawn there like that little ten-year-old girl to wander the antiquities galleries and to stare at the artifacts from ancient civilizations. I also discovered from his armor that Henry VIII was short and about as wide as he was tall. Imagining him trying to pry himself out of that plated mass much like a child who has to unbundle from a snow suit in order to use the bathroom amused me greatly.

During that time, my accidental jewelry business was born. All of the elements, images, glyphs, secrets and beauty of antiquity that had been kaleidoscopically turning and turning in my imagination since I was ten resolved into a picture. I did mention glass deer, yes? Back on Olvera Street, the first street in Los Angeles, that City of the Queen of the Angels, there was a glassblower who would, as I watched, draw out the most delicately lively little animals from seemingly dead lumps of glowing glass. I collected them, and the deer were my favourite, with spindly awkward legs that reminded me of my own. Later exposure to the artefacts of the Greeks, Romans and Egyptians gave me more glass to file in my imagination alongside those deer, and then, I found myself in Venice one Christmas perhaps eighteen years ago, and I wanted to see the famed glass works on Murano. Just to look, of course. Well. It didn't really work out that way. Fred and I came home with wine glasses that were replicas of a 14th century doge's set (Fred hated their ornate nature), with a huge modern liquour decanter of vivid, brash colours (which I hated), and with a small box of antique wedding cake beads (which I loved and about which Fred cared neither way, that being, in and of itself, a marital win-win).

For some time, I had been collecting pieces of antique brocade and silk, many from old wedding obi, a habit that had begun with a gift from the mother of my first boyfriend in 1981. Yoko, who was tiny, formidable and hilarious, thought I would appreciate that scrap of fabric, and she was right. I actually had it framed a number of years ago, and, wait for it, guess what imagery is prevalent off to the side of the beautifully rendered fish? Sigh. (I must note here that a sigh is an exhalation of breath, which one must have in order to have the next inspiration.)

And So I Began to Breathe….

Anyway, with scraps of old fabric and vintage glass beads in hand and in mind, I suddenly saw it all come together. I would make bookmarks: bookmarks that would be hand-sewn and wide, bookmarks that would be ornate and elegant, bookmarks that one might use in a family bible or a tome laid open to a different passage each day, bookmarks that were very serious about being booksmarks. And So I Did.

I brought them to school to have a little trunk show and tell, and Angela, then our lower form dean, dutifully and kindly perused them before saying, "You know, I don't need a bookmark, but if you can make another one of THOSE [pointing at the dangle], I'd love them as earrings." That stopped me cold, and I wondered.... huh....could I?

Those first years of jewelry-making were exercises in elation and futility, as many self-taught endeavours are. I didn't know what a head pin was or the difference between gold-plated and gold-filled metal. I didn't know how to tie ends off for wire or cable, and I bounced around trying to figure things out by myself. I made some pretty things (my first earrings, which Angela still has, among them) and I absently noted that many of my pieces tasted of the ancient world, but I was trying to find my voice, my way, my self in the dark with hands flailing around to make sense of where I was.

If it can be argued that it is all Angela's fault that I moved out of book-mark-maker into jeweler, there are still two more women mentors of such significance that they truly set me on the path I now follow. Working as admins in the front office at school (or rather, making sure that school actually worked for all of us, kid and grown-up alike), Elfi and Winnie would always so patiently look at whatever madness I Had Made. Each time I brought something in, they were unfailingly kind and supportive, until one day I produced some frothy and complicated necklace that I had strung/woven out of colourful glass beads. It had taken me hours to create by following a pattern in a beading magazine, and I was so very proud of it.

Elfi looked at it, looked at me, and then asked how much time I had put into it. I told her. She shook her head. "Get away from the glass," she said. "Get into gemstones. Get into metal," she said. "Get real." She then paused for a moment before adding, "And quit following patterns in magazines. It's time." I was a bit taken aback (and the beaded flowers in my frothy necklace seemed to wilt in my hand), but it was a gestalt moment, and I then began exploring the idea of daring to use actual stones and precious metals in my designs of my own making. For quite some time, I utilized manufactured silver beads and findings, and when I incorporated gold into my designs it was by way of gold-fill and vermeil, though I will admit that I was drawn to the vermeil because it was richer in colour and reminded me of the ancient goldwork that had so attracted me when I was a child.

Winnie, along with Elfi, encouraged me at each step into this strange territory, but at a certain point she, too, pushed back. I remember showing her something I had made with manufactured vermeil findings, and she simply said "You need to make that in actual gold." I was scared because, well, GOLD, but her encouragement and support gave me the guts to do it. Some long time later, I brought in a chain necklace I had painstakingly made of twisted gold wire, using a carpenter's pencil as a form (I didn't know the word mandrel then), because I didn't realize until I had done it that the blasted wire would fling itself off the pencil into a bizarre snaky twist, instead of a neatly shaped hexagonal coil. It was fun getting those links to actually behave like links, let me tell you. Live, learn, cry. Regardless of its awkward birth, and the wonky solder joins from a butane torch, she loved it. She bought it from me, and she still wears it, fifteen years later. It was at that point that I realized that I could do this.

Eventually, way led on to further way as it is wont to do. I wanted to know how to do those things that the ancient goldsmiths did, that the modern fabricators did for every prefab bead or finding that I bought, and, honestly I wanted to know how to avoid being attacked by the things I was trying to create, so, after completing my Ph.D., then in my fifth year of teaching Latin in San Francisco, I decided to become a goldsmith myself. I enrolled in the Revere Academy of Jewelry Arts and took classes from some of the most accomplished goldsmiths on the west coast, including Alan Revere himself. At the Revere Academy, the training was classical, focusing on the old European traditions of goldsmithing and I learned how to do everything from pouring an ingot and drawing my own wire to granulating with high-carat gold to create decorative motifs, which of course was that wondrous thing that I had first encountered so many years before with the Scythian gold.

In addition to the courses taught by Revere faculty, I took classes by visiting masters, and one of them, “Ancient Rings”, taught by Jean Stark, captured my attention almost obsessively: I made a Roman inverted bezel, an Egyptian scarab band and a medieval European poison ring. I look at those rings now and wonder at how I found the nerve to dare to try them at that time. Later, I learned to work with argentium silver, from fusing to 18k gold granulation, with Ronda Coryell, and I learned the ancient technique of crocheting loop in loop chain from fine silver and 18k gold, among other things, from Michael David Sturlin.

Inverted Roman Bezel with Moonstone Created in Jean Stark's Class

Bear in mind that these are student pieces with student issues. All knowledge I can lay at their feet; all errors, mistakes, misreads are mine alone. And yet, by making those errors, mistakes, and misreads, I also got to the point where I could begin to think in metal and stone. These are a few sketches in metal, works in progress, ideas in development...

Although I continue to teach classical Latin (this will be my twenty-third year at Stuart Hall for Boys) and I love working with middle school boys, my heart is divided and half of it lies at my bench. In my Marin studio, I pore and forge; I draw and fabricate; I granulate and set; and I oddly (or perhaps not so oddly at all) find that all of my designs, or at least those that work, that sing, in some way call me back to the ancient world, my first and finest love.

Still Under the Influence

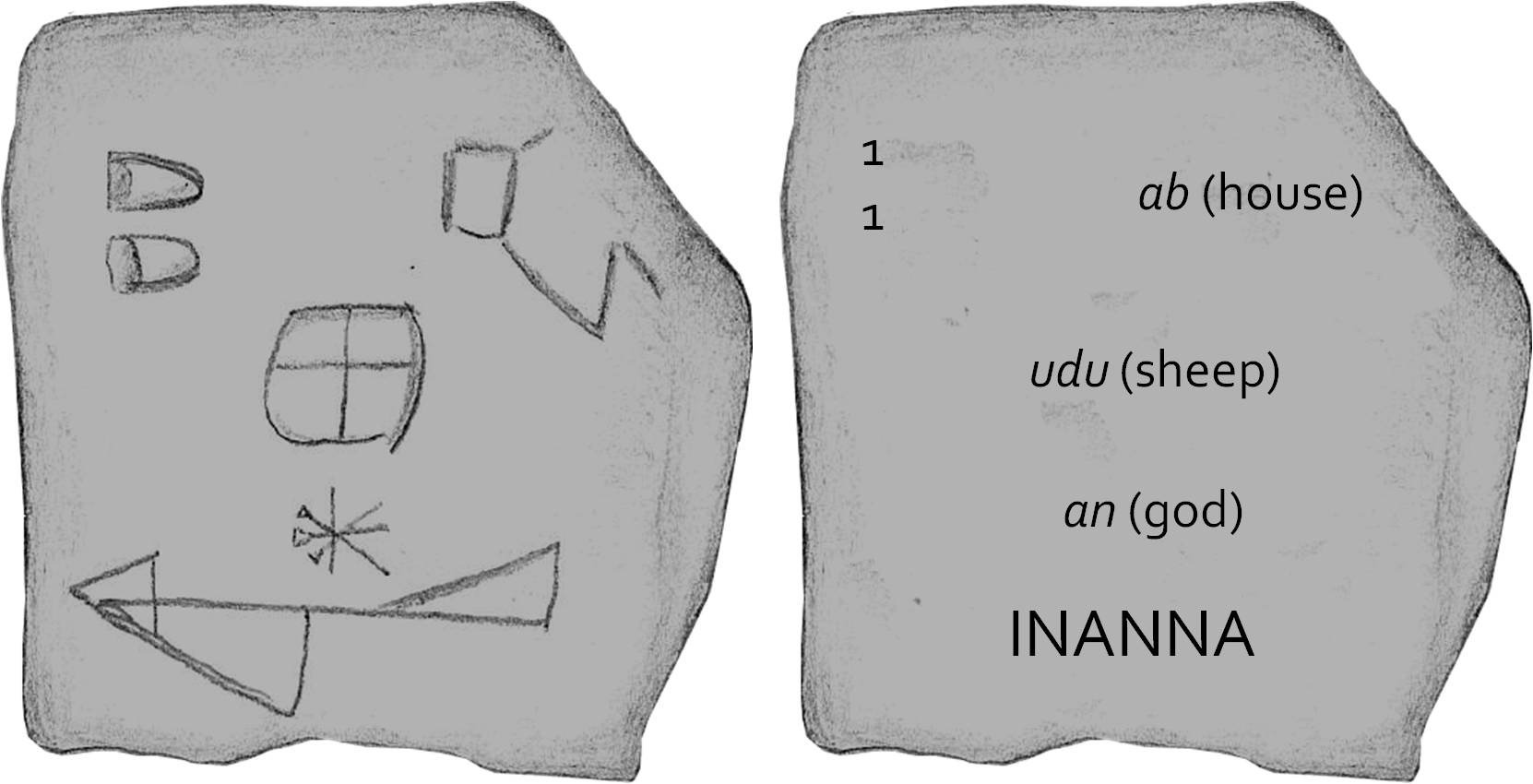

So, to finish, I offer this hilarious but sadly true story: Not long ago, I found myself under the spell of the ancient world once again, but instead of being at my bench, I was behind my steering wheel and driving right past my home exit, so far past, in fact, that I ending up a good ten miles out before I realized what I'd done. I had become so caught up in a podcast about the origins of written language that I was most likely a menace to the drivers around me on the 101 north. And what caused it? The earliest found bit of written language, a banal (in their time) temple record on a piece of clay, something equivalent to the receipt you might get from the checkout clerk at Safeway. And on that tablet, written in cuneiform by some temple scribe in Uruk, the ancient Mesopotamian city that gave its name to Iraq and is about an afternoon's drive from modern Bagdad, are four "words": Two. Sheep. God. Inanna. It was a profoundly transformative moment for me (yeah, yeah, I know, but as it turns out my studio is in my basement, so...again...hush). I had to see what those earliest words looked like, after, of course, I had turned around and actually driven (sheepishly?) home, all the while vowing never to listen to podcasts while driving because It Is Just Not Prudent.

What I found was wonderful. I loved the cuneiform, of course, but what I loved more was the possibility of story behind that simple temple receipt. Was it two sheep taken in as an offering dedicated to the goddess Inanna or was it a record of the temple priests taking two sheep from those offered to the goddess? We don't know. All we have are two sheep, one house of worship and a very powerful goddess. The glyph for god, which looks like a star, reminded me of the compass rose, of the cardinal and ordinal points of direction that we humans have been trying to sail through life by forever. "Good luck to the sheep," I thought, "that star is where I want to be." Not as a goddess, but as a witness to the beauty of that symbol, to the enduring spirit of human imagination, and to its need to communicate, to share, to record, to speak life.

And that is what I seek to do with my jewelry, both in the creation of it and in the wearing of it. I want to communicate something of the beauty of our shared ancient human experience, something of the wonder of those times and those places, so wildly diverse and yet so connected by the sheer humanness of humanity, of then and now. I want to bring a little of the magic and wonder of the ancient world into contemporary life where I hope that it sparks a connection to allow the wearer to perhaps consider that way does indeed lead on to way.